We're going to do a regular blog post shortly from lovely Aitutaki in the Cook Islands, but the issues described below are ones about which silence is unacceptable.

The question should never need to be asked: Can an atoll collapse? Answer: If you explode a couple hundred nuclear bombs on it, it can. As you might know, atolls are formed over hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of years, when old volcanoes subside and ring-shaped walls of coral grow up around them. From 1966 to 1996, the formerly inhabited Mururoa and Fangataufa atolls in the southern Tuamotus of French Polynesia were used by the French government for setting off 196 nuclear explosions. Other nations, particularly the US, have been equally profligate in their nukings of seized islands elsewhere.

According to a report by the French Ministry of Defense recently mentioned in the local press, the two atolls have been so weakened that collapse may be imminent. You might remember the massively destructive December 26 tsunami in the Indian Ocean a few years ago; it was caused by the earthquake-driven collapse of an underwater geological formation. Researchers are now saying that if one of those atolls collapses, a 15 to 20 meter tsunami wave—that's 45 to 60 feet—is possible, along with releases of radioactive materials. The local political leadership, headed by displaced Mururoa resident Roland Oldham, is saying researchers told them to "allow preparations for a worst-case scenario." Oldham also said, "We are the people concerned, we live in this area of the Pacific, and we don't have any information."

If ever a Polynesian Trail of Tears existed, this is it.

Global is local, and vice-versa: This reminds me of an issue simmering at home, in which powerful entities also get to exploit the commons—namely air, water, the soil, ancient homelands, and let's not forget the future itself—without regard for its true owners. In Port Townsend, Washington there is a paper mill, located on the shores of Puget Sound, that is one of the area's largest employers. There is also a local citizen's group that has for several years been trying, unsuccessfully, to learn what exactly is in the mill's smelly plume.

The paper mill now wants to build a landfill near the shoreline. In this landfill will be placed tons of ash with a pH of 12.3; that's ten times more caustic than ammonia. Evidently there's a legal loophole that may allow the mill to avoid the use of liners that might otherwise help keep noxious materials from leaking into Puget Sound, and into groundwater. The legal premise is that paper mill wastes are "inert." I understand that there may be a lawsuit from the mill's foreign owners against the local government if the liner exemption is not granted. If allowed, this exemption would be the only one in the entire state of Washington. This argument as I understand it isn't even over the existence of the proposed landfill, whose contamination potential has State officials worried; it's just over the liner.

Maybe this issue shouldn't be characterized as jobs versus something called "public health," which has neither name nor face. Maybe it should be put more directly, like this: The issue is about more profit right now for the paper mill's owners, versus Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in a few years for Mary, glaucoma for Joe, a brain tumor for Nancy, bronchitis and asthma spikes in kindergartners, and a reinforced belief that a mortgaged future for the many is acceptable payment for such a trivial-by-comparison thing as the savings gained by the few, from not buying a freaking liner for a landfill that's anything but "inert."

The extreme potential for disease and deformity in fish and wildlife in an area renowned for its salmon fishery is not addressed in this post.

At 6,000 miles distant, I'm at a disadvantage to fully understand why common sense seems to be missing here—after all, Puget Sound's small boat owners and small businesses are being made to clean up their acts. The questions are clear: Why is it that local stakeholders so often lack critical information pertinent to their own health and welfare? Why is there apparently a double standard? What leverage do corporations have over local governments, and why are these power struggles so increasingly common? Why don't more "ordinary" citizens speak up to support their local leadership? On leadership's part, where is the courage? Why do you not demand that the commons, namely our air, water and soil, be figured into economic equations? What about the economic value of staying healthy rather than treating preventable illness—should that not also be in the mill's balance sheet? How often is a scene like this being repeated right now, not just in the US, but around the world?

Doing the right thing sounds simple: Tell the people what they need and have a right to know, when they need to know it. No exaggeration, distortion, censoring or blocking of information can afford to exist on any side. Stakeholders are responsible for keeping it honest. Invest in cleaner practices now, for reasons too obvious to explain. Put a monetary value on "ecosystem services" such as the commons provides. This is easier said than done, but it is not impossible. Include these values in economic equations when considering permits to pollute. A permit is a privilege, not a right.

Apathy and intimidation are the blunt weapons of choice for powerful interests, especially non-local business owners for whom profit is the exclusive goal. Hand-wringing won't solve anything when your back's against a wall. The high cost of low trust is far too much to ask a small community to bear, because human health should not be allowed, at any level of government, to become an expendable commodity in a corporate business plan.

A corporation is not a citizen, in spite of what the US Supreme Court said. But the way some corporations are behaving these days, it's curious as to why the Supremes don't find them in contempt.

Doing the right thing may sound simple, but it seems these days more than ever, the devil's in the details.

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

Friday, August 3, 2012

Epic Sail!

At sea between Bora Bora and the Cook Islands: The trade winds are booming, and the boat's making good time--108 miles in the first 24 hours! Of course the minute I say this, two things will happen: 1) everything will stop, except for 2) the waves, which will still splash us. (As I was reading the draft of this post to Jim, a wave splashed down our companionway--see?) Hatchboards are now blocking any more waves. Sailors consider it bad luck to be superstitious, so you have to come right out with this stuff. Who knows, maybe this will be a nice, fast, not too rough passage. Aitutake atoll, our destination, is in the Southern Cooks, which are administered by New Zealand, which means the default language will be English, not French, which could take some getting used to, n'cest pas? French Polynesia was mighty good to us, and we'll always want to come back.

Last night saw us reefed all the way down to a double reefed main and staysail only, not even a tiny scrap of genoa. But wow did we go! Aitutake's got a tricky entrance channel that keeps boats drawing 6 feet or more out, so we feel the luck of the small-boat sailor in being able to go there.

Our last night in Bora Bora was spent at anchor next to our buddy-boat, Buena Vista, whom we've mentioned in previous posts. (Wait'll you see the photos of snorkeling in the lagoon!) We four friends spent an evening saying goodbye until we meet again (in Tonga, we hope), and yesterday morning it was sad to watch Don and Deb sail over the northwest horizon while we sailed southwest. They're bound for Suvarov and American Samoa, to take delivery of a sail (a genoa) to replace their "old" one which, through no fault of theirs, fell apart in less than 2 years. Some sail misadventures, such as Gato Go's mainsail tear in a 60-knot squall on the crossing are understandable, but other stories of old sails in such poor shape that owners are constantly mending them have a Ground Hog Day look about them. That's not what happened with Don and Deb, however; they did everything right, and that's what's so unfair in this case. Two years ago their sailmaker recommended and built them a big, tri-radial roller-furling genoa from crinkly lightweight cloth as their main headsail for a trans-Pacific voyage. Just north of the Equator it split along a 20-foot vertical seam, which lengthened Buena Vista's passage considerably.

By the time the umpteenth repairs were done on it last week at the Bora Bora yacht club, there were so many seam rips that it became obvious this sail was experiencing a catastrophic failure. I was able to break a piece of sail thread by hand, and a needle poked into the fabric would tear it easily. Dozens of hard spots where fabric tears were beginning could be seen all over the sail, and the overlap workmanship on seams was done so poorly that that the sailcloth's warp and weft were separating along multiple seams, at 5, 10 and 20 foot lengths. It was literally coming apart! We didn't have enough sail tape to cover all the rips, so Deb used white duct tape, which we tacked with stitches over seams after sewing the seams back together as best we could--truly a git 'er home repair. Luckily, Ed and Fran aboard the 39-foot Aka loaned their spare genoa to the 46-foot Buena Vista, and it looked like a Yankee (high-cut headsail), setting well as Don and Deb left Bora Bora. The Epic Fail Sail could still be flown drifter-style if they get becalmed. But it's not to be trusted.

I wouldn't know where to start in describing the emotions such shoddy workmanship can provoke, but try fear when you're a thousand miles at sea, frustration in mending it again and again, and then anger in having to divert hundreds of miles to American Samoa on a borrowed sail because the sailmaker refused to ship the replacement to Tahiti as previously promised. Deb and Don have been models of patience. I, on the other hand, would like to plaster this sailmaker's name in neon after seeing what he put them through, especially the hard time he gave them when they sought redress. But I won't. Suffice that he's not a well known name--I had never heard of him--and you aren't likely to encounter him outside of Southern California.

This is a cautionary tale. Sailmakers are cruising partners with their customers, and the good ones stand by their work. That's because the good ones know what's at stake when you go to sea, because, and this is important, they've been out there and have learned from it.

Sent via Ham radio

Last night saw us reefed all the way down to a double reefed main and staysail only, not even a tiny scrap of genoa. But wow did we go! Aitutake's got a tricky entrance channel that keeps boats drawing 6 feet or more out, so we feel the luck of the small-boat sailor in being able to go there.

Our last night in Bora Bora was spent at anchor next to our buddy-boat, Buena Vista, whom we've mentioned in previous posts. (Wait'll you see the photos of snorkeling in the lagoon!) We four friends spent an evening saying goodbye until we meet again (in Tonga, we hope), and yesterday morning it was sad to watch Don and Deb sail over the northwest horizon while we sailed southwest. They're bound for Suvarov and American Samoa, to take delivery of a sail (a genoa) to replace their "old" one which, through no fault of theirs, fell apart in less than 2 years. Some sail misadventures, such as Gato Go's mainsail tear in a 60-knot squall on the crossing are understandable, but other stories of old sails in such poor shape that owners are constantly mending them have a Ground Hog Day look about them. That's not what happened with Don and Deb, however; they did everything right, and that's what's so unfair in this case. Two years ago their sailmaker recommended and built them a big, tri-radial roller-furling genoa from crinkly lightweight cloth as their main headsail for a trans-Pacific voyage. Just north of the Equator it split along a 20-foot vertical seam, which lengthened Buena Vista's passage considerably.

By the time the umpteenth repairs were done on it last week at the Bora Bora yacht club, there were so many seam rips that it became obvious this sail was experiencing a catastrophic failure. I was able to break a piece of sail thread by hand, and a needle poked into the fabric would tear it easily. Dozens of hard spots where fabric tears were beginning could be seen all over the sail, and the overlap workmanship on seams was done so poorly that that the sailcloth's warp and weft were separating along multiple seams, at 5, 10 and 20 foot lengths. It was literally coming apart! We didn't have enough sail tape to cover all the rips, so Deb used white duct tape, which we tacked with stitches over seams after sewing the seams back together as best we could--truly a git 'er home repair. Luckily, Ed and Fran aboard the 39-foot Aka loaned their spare genoa to the 46-foot Buena Vista, and it looked like a Yankee (high-cut headsail), setting well as Don and Deb left Bora Bora. The Epic Fail Sail could still be flown drifter-style if they get becalmed. But it's not to be trusted.

I wouldn't know where to start in describing the emotions such shoddy workmanship can provoke, but try fear when you're a thousand miles at sea, frustration in mending it again and again, and then anger in having to divert hundreds of miles to American Samoa on a borrowed sail because the sailmaker refused to ship the replacement to Tahiti as previously promised. Deb and Don have been models of patience. I, on the other hand, would like to plaster this sailmaker's name in neon after seeing what he put them through, especially the hard time he gave them when they sought redress. But I won't. Suffice that he's not a well known name--I had never heard of him--and you aren't likely to encounter him outside of Southern California.

This is a cautionary tale. Sailmakers are cruising partners with their customers, and the good ones stand by their work. That's because the good ones know what's at stake when you go to sea, because, and this is important, they've been out there and have learned from it.

Sent via Ham radio

Friday, July 27, 2012

Where We've Been and Where We're Going

Where we've been: Here's the route we've sailed since leaving Port Townsend, Washington on July 9, 2011: nearly 7,000 miles! When we think about how far we've come, it feels like yesterday for some things and forever for others. For example, San Francisco Bay or Mexico feel like yesterday, but it does feel a little like forever since we left Port Townsend. Thank goodness for blogs to keep in touch with our homies. Why is it that the more full you pack a year, the longer it feels? I believe we may actually be expanding time, maybe even getting younger (!!) by making this voyage. There also remains that "Whoa, did we really sail here?" feeling on most days. Woo-hoo!

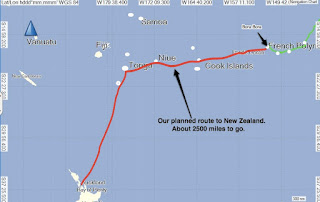

Where we're going: Here's a map of where we're going for the rest of this year, the destination being New Zealand. The piece of ocean we'll be crossing between here and Tonga is where South Pacific cyclones are born, but it's not that season right now, so we should be able to cross it safely. The winds can get boisterous, but that's to be expected. Boisterous is not cyclone force. Between May and October this area is not cyclonically active. But as you probably know by now, weather or whimsy could change our route across to Tonga.

You rock! We'd like to express our appreciation to readers, followers, and especially commenters on this blog and via email. It's so satisfying to stay in touch with old friends and make new ones. It's also satisfying and fun to hear from sailors who dream about voyaging or are actively getting their own boats ready for a cruise. Having dreamed about doing this cruise for many years, I (K) can identify with making those long-term plans. This blog is about staying in touch, making new friends, and telling stories. Thanks for sailing with us.

One subtlety about this "lifestyle" is that although it might look like one big jolly continuous vacation to some, it's not always a party (of course you knew that.) It's how we live, with emphasis on play. If we tried to be on permanent vacation, we'd exhaust ourselves. Our cruising buddies Don and Deb Robertson on Buena Vista help us remember how to keep it in perspective: when the solar charge controller goes on the fritz, or the dinghy springs a leak, or the outboard balks, or the head needs repair, it's a good time to shout at each other across an anchorage, "YOU are livin' the dream!"

Tuesday, July 24, 2012

Tahiti to Bora Bora

We're in Bora Bora, nearly at the end of our visit in French Polynesia. Most of our time in FP was spent in the Marquesas. We chose to see just one atoll in the Tuamotus (Fakarava), and felt quality over quantity was a good decision.

Finally, we sailed to the Society Islands group (Tahiti,

Moorea, Raiatea, Bora Bora and more.) Here’s

where we were in Papeete harbor.

We wish we had more time to properly see the Iles Societies,

but all in all, it’s been a terrific three months, which is the maximum amount

of time the French allow Americans and Canadians to stay unless special,

labor-intensive and very expensive arrangements for a long-stay visa are made

before leaving the US. I think it has

something to do with a political fight on Capitol Hill years ago, over freedom

fries.

Although some of the street signs were a little weird (no one could tell us where to find the Culte of Silence because… it’s silent) we found the people of French Polynesia—all of them—to be polite, smiling easily and often, especially if you try to speak just a few words of their languages (French, Marquesan, Tuamotan, Tahitian.) And who wouldn’t smile living in this lovely climate?

We finally rendezvoused with our Oregon-based friends Mark

and Vickie of S/V Southern Cross, an

Ericson 38, and spent an enjoyable day with them touring the island. There are many things to do in Tahiti. For example, you can swing on a vine.

You can drive (or hike) up the mountain to a gorgeous

lookout over Papeete harbor with Moorea

in the background. That’s Mark and

Vickie with Jim.

You can visit Point Venus and see the lighthouse near the

spot where Captains Cook and Bligh observed the transit of Venus.

There are some interesting ways of storing outrigger canoes

there, too.

You can sunbathe on a black sand beach if you don’t mind the

two-tone look afterward.

You can watch kids play near a waterfall.

And you can watch local fishermen bring in the pestilential

crown-of-thorns starfish, which are both poisonous and invasive, causing great

damage to reefs. You can’t just chop

them up and throw them back, or each piece could regenerate a whole animal; you

have to dispose of them on land. A recent article in the New York Times describes the perils that coral reefs around

the world are facing.

While we’re at it, here’s a shot of the damage that goats

can do to an ecosystem—the fenced-in area where they live has been completely

denuded of vegetation.

You can go to the market at 6:30 am to find bustling crowds.

You can talk to other cruisers—these guys own the only boat

registered and berthed at Easter Island, and they were preparing to sail back

there (to windward, yeeks.)

You can indulge in some Tahitian fast food; this man’s roadside

drinking coconuts were tasty.

Or you can go to the Hieva Celebration, which is French

Polynesia’s 130 year-old national singing and dancing competition. When 200 tattooed, scantily clad dancers take

the stage backed by a 40-member drum band with attitude, you know you’re not in

Kansas anymore. Photos weren’t allowed,

but just google Hieva Tahiti images, and you’ll see what we mean. It was a terrific way to spend an evening. Made me want to do the hula and get tattooed.

You can also read about somber subjects, such as the 193 atomic

bombs dropped over a 30-year period by the French on Moruroa and Fangataufa

atolls, which does not even begin to count the horrific number of nuclear

explosives dropped by the US and other nations on “remote” atolls that were

actually peoples’ homes, throughout the Pacific, and about the continuing

effects on marine and human health. This

is a memorial to all those places.

Mark and Vickie hauled their boat in Port Phaeton (below) a

sheltered bay between Tahiti and Tahiti Iti, to be stored until they can return

next year, to continue their voyage.

We kept Sockdolager

at the downtown docks in Papeete for almost two weeks.

Photo by Karen Helmeyer

This was in part because the charms of a “big” city were

irresistible, and part because of a windstorm that blew in and made us decide

the docks were a better place to meet our Hawaiian friend Karen Helmeyer, who

joined us for a week of sailing.

Jim nicknamed her K2.

The two Ks are best buds from an intensive course both took years ago at

Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. When

we meet other people and they say, “You’re both

named Karen? How convenient!” we say, “Yeah, we’re sisters who were

separated at birth.”

Sockdolager was

med-moored in Papeete with her bow facing the dock, and we got ashore by

walking on a tightrope from the bowsprit to the dock. The minute you step on the tightrope it sags,

which for a first-timer is not a welcome surprise. But nobody took a bath.

Although quarters were a bit tight aboard the old Sockdolager, everyone coped with good

humor and downright hilarity at times. Besides

being a fellow fracturer of English, French, Spanish and other languages, Karen2

also has the enviable quality of enjoying a cast-iron constitution, which means

she never gets seasick—yippee! Here she

is in big seas, wearing her Florence of Arabia hat.

Fwactured Fwench: Language was mercilessly butchered in our

linguistic laff-off. I wouldn’t know how

to begin writing the mispronunciations of some French words we tried, but Jim

takes the cake for his one-phrase-fits-all approach:

Clerk at grocery store:

Bonjour!

Jim: Bonjour!

Clerk, handing him change:

Merci!

Jim: Bonjour!

Clerk, staring oddly at Jim:

Au revoir!

Jim: Bonjour!

Karen2 marched up to a young clerk at a convenience store at

the fuel dock and asked him in perfect French, “Do you need a hearing

aid?” Then she turned to another man and

rattled off, “I have missed my train, and do not know what to do with myself!”

It pretty much stopped all conversation, since there are no trains in Tahiti

and everyone heard her perfectly. Then

the giggles began. Berlitz phrase books

contain the most useful phrases for

gringo travelers!

Breakfast cereal became Amuesli; a bruised knee to which no

memory of the thwack could be summoned was declared a case of Amkneesia. Any clothing worn to keep warm in is known as

Snivel Gear.

We made a few visits to our favorite waterfront brewpub, the

3 Brasseurs, which we immediately renamed the 3 Brassieres. At another one called the Pink Coconut, a cruising

couple from Beausoleil (the cookbook

authors) hailed us while we were talking with a pair of friendly sailors named

Larry and Nelda at another table.

Suddenly I realized that ALL the women who were about to introduce

themselves to Larry and Nelda were named Karen.

“Hi, I’m Karen.”

“I’m Karen, too.”

“Um, my name’s also Karen.

Seriously.”

“Wait. THREE Karens?”

said Larry.

“Yeah, we run in packs.

It’s a Karen thing.”

Photo by Karen

Helmeyer

Tahitian Rulottes

are something you must try if the chance ever presents itself. In the Army, as Karen2 (a retired Colonel)

told us, these rolling restaurants would be called roach coaches or maggot

wagons. Yuck! I’m such a civilian! But they were clean, the smells were

delicious, and my appetite returned. Every

evening at six about a dozen large vans roll into a Papeete waterfront park and

begin cooking. There’s Chinese cuisine

six ways to Sunday, plus crepes wagons, pizza-mobiles, and one van offers a

whole roasted mammalian species (either goat or veal) spread-eagled on a

rack. You walk up to the carcass, you

order the cut, and they whack off a Neanderthal-sized chunk to your plate. Whew.

I passed on that one, culinary wuss that I am. We 3 loved the “Hong Kong” rulotte’s

excellent Chinese food, and nearly died of ecstasy sharing a Nutella crepe at

another rulotte. Nutella crepes. It’s what’s for dessert from now on.

Photo by Karen

Helmeyer

Crossing an active airport

runway is always a dicey thing, but crossing it in a slow-moving sailboat

is extra exciting. The short runway at

Faaa airport (pronounced Fa-AH-ahh) ends abruptly at the edge of a narrow boat

channel. Here’s how to cross it:

“Papeete Port Authority, this is the sailing vessel Sockdolager, requesting permission to

cross the runway.” Good god, did I just ask to cross an international airport runway in a

sailboat?

“Sock… Sock… vhat is your boat’s name, please?” (Heavy French accent.)

“This is Sockdologer (I’m giving it a French spin, saying

something that sounds like “SuckdoloGHEARH.”

It works.)

“Ah, SuckdoloGHEARH, yes.

You may cross now, zhere are no planes landing for zhe next few meenoots. Please call me back vhen you have crossed zhe

runway.”

“Roger, sir, we will call you when we have crossed.” If we

don’t get sucked into a 747 engine, that is…

A brief stay at the anchorage at Maeva Beach/Taina gave us

the chance to see our friend Shane aboard Clover

again. Here he is, with tattoos all

freshened up by a Marquesan artist. He’s heading for American Samoa. We also got an email from Craig on Luckness, and he’s making good progress

from Hawaii to Seattle. Zulu is either enroute or probably about

to leave Hawaii for Seattle, too. Who

knows when we’ll all be reunited again?

Photo by Karen

Helmeyer

We especially love this photo—Shane (in dinghy) versus the

mega-yachts. Our money’s on Shane.

Photo by Karen

Helmeyer

Tahitian canoers love to “backdraft” on a boat’s wake, which

helps them go faster with less effort.

Karen2 declared that she was ready to propose to this hottie.

Photo by Karen Helmeyer

The sail to Moorea started out calm, but ended with us

double-reefing the main and genoa. It

was one of those Whoooeee-look-at-us-go! sails.

But Moorea, oh my. One of the

most lovely places on the planet. And can K2 take good photos, or what?

Photo by Karen Helmeyer

Okay, folks, here it is, the official Tattooed Ladies Photo:

Did we really get tattooed, or are they just temporary? Would we really do this? Ya think?

C’mon, let’s have your opinions.

Dancing with the

Stars: The tattooing sessions were

followed immediately by a hula session, in which the dancers pulled several

people from the crowd, mostly types who don’t mind making fools of themselves. Of course both Karens got up and made foolish

fast. Witness this photo of K2 photo-bombing

herself:

And, a more sedate K1 does some vague hybrid of hula and

monster mash.

Mega-Yacht Surprise: We thought our brief stay at Cook’s Bay in

Moorea couldn’t get any better, but it did:

one evening we went to dinner at a waterfront restaurant where a

Scottish singer-sailor-autoharp-harmonica player named Ron was getting ready to

entertain with oldies and folk tunes. At

the front desk a smiling woman named Arlene handed us menus, which would make

anyone think she worked there, right?

She said we’d really enjoy the

food and the music, so we stayed. We

liked Arlene and Ron right away. Turns

out she doesn’t work there, but was instead visiting Moorea aboard a 178-foot sailing

yacht in the harbor, named Tamsen. It quickly became obvious that she and Ron were

madly in love. A-HA! The plot thickens!

But magic was in the air for everyone that night. Ron and Arlene joined us at our table for a

few minutes of delightful talk, and the next thing we knew I was on stage with

Ron, belting out “Summertime” without a nanosecond of rehearsal, and loving

it. Sometimes a song just slides out of

you, almost singing itself—that’s how it felt.

The audience, about 40 of the 60 people aboard Tamsen, loved it too, and I got up several more times to sing and

harmonize with Ron. When I returned to

our table, Jim and Karen2 told me that Bob, the owner of Tamsen had invited us aboard for a visit the next day.

Here’s Tamsen in

daylight and all lit up at night. Her

lines are quite graceful and the high level of maintenance is obvious. Look up her web site here. A nice writeup in the New York Times is here.

If you’ve been following previous posts, you know that we’ve

been rather critical of the behavior of some of the mega-yachts encountered

along the way. Most have been

snooty. Some have behaved badly. This story will prove that every assumption

has an exception, and what an exception this was. Aboard Sockdolager,

the 2 Karens dolled themselves up a little; then we 3 got into our tiny dinghy and

motored grandly up to Tamsen,

figuring we’d need to explain to the crew that “Bob” had invited us aboard, and

then we’d wait like three gnats at the waterline until they fact-checked

it. Well we were in for a surprise. There weren’t any crew in sight, it was all

family and friends. And Bob, his son

Steve, and half a dozen other family members were waiting for us, waving! We’ve seen 200-foot motor yachts that have 17

crew waiting hand and foot on just a couple of people, but we’ve never heard of

a yacht this size being run almost entirely by a happy, noisy horde of 60 family

members and friends, including mobs of kids.

The first thing that astonished us was not the magnificence

of the yacht but the warmth and genuine pleasure every single person aboard Tamsen expressed at our visit. Without exception each person greeted us and

wanted to know more about us. We were

made to feel as welcome as family members.

Bob and Steve, along with several other family members, led us on a tour

of the ship that was great fun (and so jaw-dropping I nearly needed a head-sling.)

Karen2, by now the Official Sockdolager Staff Photographer,

took some photos, so come along and we’ll take you with us. Let’s start at the mainmast. That’s Bob Firestone in the gray T-shirt, and the crowd around Jim and me are his family members and

friends. Everything on the ship was

custom-built in Italy, from the steel hull with its aluminum

superstructure to the rigging and interior cabinetry. Bob’s son Steve Firestone

serves as Captain, and he knows every inch of the vessel because he supervised

its building.

Photo by Karen

Helmeyer

Here’s a clean foredeck.

Photo by Karen

Helmeyer

Just behind the foredeck are boat wells for each ship’s

tender, but we observed that Sockdolager

could probably fit in one of these without too much trouble.

Photo by Karen

Helmeyer

Here’s a dinghy being lowered into one of the wells.

Photo by Karen

Helmeyer

You want rigging? BrionToss and Gordon Neilson, this photo’s for you. Much of the running rigging is Spectra, which

is far stronger than nylon or dacron, which means you can use a smaller

diameter line; still, the genoa sheets were twice as thick as Sockdolager’s

anchor rode. Steve said, “It gets pretty

scary on the side deck when this sheet whips around.”

Photo by Karen

Helmeyer

To gild the lily: another rigging shot, under the main boom,

which houses the furled mainsail. The

boat’s working sail area is about 6000 square feet. The mainsail weighs more than a thousand

pounds. Everything is mechanical: the stresses are far too big for humans to raise

or trim sails by hand.

Photo by Karen

Helmeyer

Here’s the control room for mechanical propulsion. With its windows looking over the engine

room, it reminded me of a recording studio.

Or the cockpit of the space shuttle (not that I know what one looks like).

Steve knows every inch of the engine room, too.

Photo by Karen

Helmeyer

Here’s Karen2 at the helm in the wheelhouse, though the helm

on a ship this size is actually a joy-stick and wheels are seldom used.

Left to right on the stern deck: Karen Helmeyer, Bob Firestone, Karen

Sullivan, Jim Heumann, and Steve Firestone.

Lin and Larry Pardey, this photo

is for you: Steve asked us if we

knew you and we said yes; then he told us that he and his crew aboard the schooner

Vltava once towed you through the

Suez Canal! The Tamsen crew is the same group of teenagers who sailed Vltava around the world in the ‘70s, and

they asked us to send you a fond hello!

We were shown through every inch the interior of the ship,

too. Here’s the busy galley, where the

kitchen watch-of-the-day was preparing a meal for 60.

Photo by Karen

Helmeyer

To give you an idea of how such a boisterous crowd is

organized to run a ship, which is somewhat like running a small city, below is

the Dock Watch List that Steve came up with.

There are 5 watches of 10-12 people each, with duties covering

everything from a 24-hour anchor watch to cooking, cleaning, manning the swim

platform, and running the tenders.

Bob said, “We’re not what you’d call sedate. When we pull into harbor, the other

mega-yachts groan, oh no, not them again!”

“Are you saying,” I asked, “that when Tamsen drops anchor, it’s ‘There goes the neighborhood’?”

“Absolutely,” said Bob, to guffaws.

We were amazed at the level of organization. On major ocean passages they don’t take 60

people, of course—just a few sailing-savvy friends and family, along with their

half-dozen permanent, paid crew, several of whom are lifelong employees.

Although it’s a big boat, there are not enough cabins aboard

to give every married couple privacy in a party of 60, so they set aside a nice

dark room nicknamed, if I recall correctly, the “consummation cabin.” It’s near

the laundry room, and the adults book time in it. Seriously.

There was much hilarity as one of the women opened the door and the

young couple inside dived for cover.

“Good grief!” I said, Does this door not lock?” Desperately trying not to look like a voyeur,

I shielded my eyes and backed away, but they said, no really, you should see this cabin!

“If you don’t lock it someone will probably open it!” was

the amused consensus. I tried to

apologize to the young couple for intruding at such a tender moment, but all the

laughter drowned out the attempt. Wowzer!

Half an hour later as we toured the enormous main saloon,

Bob told us the story of how, back in the ‘70s, he got a dozen families to

partner and buy a 74-foot wooden staysail schooner, called Vltava, and let their 11 teenaged children sail it around the world

by themselves. It was Bob’s idea for forging stronger bonds

of trust and confidence, in kids who otherwise might have taken a different

track in life, and it worked beyond all expectations. Steve was elected captain, even though at 16

he was not the oldest. They made a documentary

movie of the unusual Eastabout, 17-month circumnavigation, called “Voyage to

Understanding,” and a couple dozen of us gathered to watch it on a big screen. The family hadn’t seen it in awhile and

decided it was time to view it again.

Those kids (and now their extended families) have stuck together ever

since; in fact most were aboard that day.

In storied families with names that are household words, you don’t

expect such warm welcomes, but aboard Tamsen,

we felt like part of the family. Here’s

the happy crew of the smallest boat in the harbor leaving, with fondness, the

largest.

Photo by Karen

Helmeyer

Time to get going: We sailed to Moorea’s Oponohu Bay to swim

with and feed sting rays, but the wind was so strong it stirred up a chop that

would have unbalanced us—and stepping on a sting ray is a very bad idea. Reluctantly, we abandoned the effort. But Oponohu Bay was gorgeous. Here’s how we always enter a harbor these

days, whenever there’s a pass to negotiate.

Photo by crew of

Vulcan Spirit

I’ve always wanted to take this photo:

…because of this photo, which has been an inspiration since

the ‘70s:

That’s the legendary Eric Hiscock on the fordeck of Wanderer

IV, with the famous Tiger Tooth overlooking Robinson’s Cove ahead. We dropped anchor in Robinson’s Cove and had

it all to ourselves.

Speaking of

photo-bombing: I forgot to mention

that as the two Karens were dinghying across Cook’s Bay back to Sockdolager after visiting the craft

fair again, another one of those disgusting giant flying cockroaches flew in

and landed on, OMG, my NECK. AAAA! AAAA!

You never heard such a shriek. I

brushed it off and it landed on Karen2.

More AAAA! AAAA! With both of us shrieking and making wild arm

motions and zigzagging with the outboard to elude the kamikaze cockroach, which

continued to buzz us, we returned wild-eyed and breathless from our

death-defying escape. Jim was, as

always, nonchalant. There was no time

for a photo, but I swear the danged thing was four inches long.

Okay, time to really get going: We left Moorea for the 140-mile sail to Bora

Bora, and made it in 31 hours. The first

24 hours were windy. Average speed was

4.7 knots, but we surfed frequently on the big swells, reaching 8+ knots

regularly and twice more than 10 knots!

Not bad for a 21-foot waterline.

Here, Karen1 plots the course on a paper chart, as backup to

our electronic navigation.

Photo by Karen

Helmeyer

Here’s Jim up in the rigging again as we enter Bora Bora’s

pass. Being up high is a good thing when

coming through unfamiliar coral passes—even the wide ones.

Here’s the Bora Bora Yacht Club, where we are currently

staying on a mooring.

Where to next? The piece of ocean between French Polynesia

and Tonga is about 1400 miles wide, dotted with islands that have narrow passes

or no passes. It’s a challenge because

of the weather (fronts coming up from New Zealand,) and the navigation; especially

for its lack of large, easy-entrance harbors.

The Pardeys and others write of being hammered in “squash zones” there,

so we are working with a voyage weather forecaster in New Zealand, who emails us

weather information for a fee. Our

strategy is to try and cross it in several hops, none of which is more than 450

miles long. But if a harbor cannot be entered due to weather, we will continue on.

The original plan was to head for Rarotonga in the Southern

Cooks, but instead we’ve decided to go to an atoll about 180 miles north of it,

called Aitutake. Rarotonga has

supposedly just finished a major harbor dredge and reconstruction, but the

rumors about space availability are so confusing that we thought let’s stay

further north in perhaps better weather, and go to an atoll, albeit with a

difficult entrance, but one where we can’t be crowded out by large boats

because its long channel has a 6-foot controlling depth. We draw 4 feet. Here’s a view of that long coral

entrance channel at Aitutake:

After that we might sail to uninhabited Beveridge Reef, to

try some snorkeling, and then, to the tiny island of Niue, of which we’ve heard

so much good about. From Niue it’s only

250 miles to Tonga’s maze of islands, which we are looking forward to

exploring. But remember, the sea is

changeable and sailors must adapt, so except for the goal of reaching Tonga,

there’s no guarantee we’ll stick to this crossing plan.

As always, we’ll keep you posted as best we can, via blog

updates by Ham radio, or the internet when it’s available.

Just as Jim paid for the bellyflop above, I just know I'll pay for the shot below, but what the heck.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)