The atolls of the Tuamotus are as different from the islands of the Marquesas as aardvarks are to ice cream. (Well, YOU try to think of a better analogy than fish and bicycles.)

This is the main harbor at Ua Pou, our last stop in the Marquesas. Sockdolager

is anchored astern of the 84-foot cold-molded wooden gaff schooner Kaiulani, homeported in Hilo and San

Francisco. (Just look for the smallest boat.) We enjoyed spending time with

her owners and crew, and especially liked the fact that both boats were

designed by the same person: William

Crealock. Kaiulani, his largest one-off design, was his favorite, and the

Dana 24, his smallest, is arguably the most beloved.

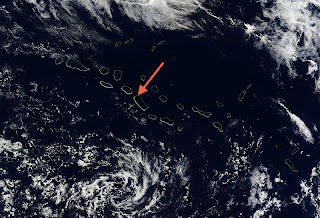

This is a typical atoll in the Tuamotus. Where the Marquesas are craggy, jungle-y mountains at 9 degrees south latitude, the

Tuamotus, at 16 degrees south, are narrow rings of palm-fringed coralline sand

with immense reefs, surrounding 30 mile-wide turquoise lagoons. Max elevation is about six feet. The main attractions in the Tuamotus are

under the water’s surface, and this archipelago is one of the finest places

anywhere for diving and snorkeling. Look

up how atolls are formed. It’s

amazing to think they’re the tippety-tops of sunken volcanoes, with the lagoons

being where the craters once were.

Our friend Marty From Prince Rupert asked us to please

identify exactly where we are next time we post, and also to look skyward and

wave so he could Google Earth us. Dude,

look at the arrow pointing to the northeast corner of Fakarava. Can you spot us?

Ua Pou was pleasant and we spent nearly a week there. The island’s jagged volcanic necks poked the

sky like spines on a dinosaur’s back, and clouds snaked around them. We saw several old friends at Ua Pou, and

made some new ones.

In spite of the calm, we managed to creep 35 miles, mostly

on a favorable current. Of course, Jim

tried to “purchase” some wind with cheap coins, which Neptune nearly tossed

back. Then he tossed in something

weightier: 100 francs. We can confidently report that 100 francs

will buy you 25 to 30 knots on the nose.

Which is why, while I was writing a blog post for the Ham radio, I had

to stop due to the need to cope with the weather, and all you got was that little 'we've arrived' blurb, before twelve-hour naps restored us. By now you should know that when you see one of those, it's safe to assume we do not want to be awakened.

Still learning to

sail the boat: We were entering the

archipelago, smack in between a small island called Tikei and two large atolls

called Takaroa and Takapoto. The wind

from a frontal system further west quickly came up from the south. The frontal system followed.

At first it was a nice reaching breeze, and in the draft I

wrote: “We are right on our rhumb line

and can see Tikei Island off to port, but cannot see two big atolls--Takaroa

and Takapoto—in our lee, off to starboard.

The wind's about 10 knots from the SSE, making this a beat to windward,

but the chop's not too big yet. The wind should ease east sometime in the next

day, too. Maybe 100 francs was just the

right amount of wind to buy after all. We're doing about 3 to 3.5 knots, and

there are 100 miles to go to Fakarava's north pass.”

Ha Ha Ha! The wind should ease! Good one.

Shortly after we began “coping,” the wind “eased” from 10 to 25 knots

with higher gusts (on the nose), and the light chop went to 6 to 10 foot seas closely

spaced, in darkness.

Thinking the double headsails were contributing to the lee

helm, we doused the genoa and went under staysail and double-reefed main. Several years ago in the Queen Charlottes, we

had easily sailed to windward in 30 to 40 knots of wind, but with no seas—we

were behind a rock reef in calm water back then, and it was amazing to see the

boat scoot like that. But in these big

seas between atolls, the helm was alarmingly mushy as the seas stopped us cold. Sockdolager

couldn’t regain momentum in time to weather the next wave because they were so

close together. There was so much lee

helm that we actually checked over the side with a flashlight to see if we’d

snagged something and were dragging it.

We hadn’t. We just couldn’t sail

to windward anymore in that mess using our normal rig for that wind speed.

Every boat has its point of wind speed and wave size where

it will no longer be able to sail to windward, and we reached ours under this

particular sail combination (double-reefed main and staysail) at about 25 knots

and 6 to 10 foot seas closely spaced.

Though it was no picnic, it wasn’t out of control—just uncomfortable.

Finally, we realized what was actually happening. Because it was the first time we’d bumped

these limits, the normally sensible strategy of reefing to lessen heeling and

increase speed did not seem flawed at the time, but it was. When seas knock you into immobility and you

need to get to windward, you may need more, not less sail, or you won’t recover

your momentum after each wave. I suppose

if the waves had spread out further, or grown larger so that we could climb

them like hills instead of being slapped, our ability to sail to windward might

have improved.

Options: One strategy was to give up on Fakarava and

run a hundred miles off the wind to Ahe or Manihi atoll, but we didn’t like

that idea. Another option was to resume

our original sail configuration, which would have allowed us to punch into the

weather, but at the cost of being severely over-canvassed. In an emergency this is what would have to be

done, but it wasn’t an emergency, because we had 12 miles of sea-room and other

options for not drifting down on the reefs.

A third option was to use the engine.

Results: We motorsailed upwind, back to our rhumb line

between the atolls. A couple gallons of

diesel worked like a charm, and we’ll still have enough to explore Fakarava and

later, get into harbor at Tahiti. Soon

we were in the lee of Kauehi atoll, just a couple miles offshore, and the seas

subsided. I should say that the boat did

magnificently under the circumstances, which forced us to learn the upwind

limits of a 21-foot waterline in that particular wind and wave signature. Larger boats might have larger limits

depending on design, but usually a longer waterline can punch through more that

a short one. We also know we could have

sailed out of there if we’d had no engine.

It reminds me of the story by Cap’n Fatty Goodlander, of having to

deliberately over-canvas his boat to claw off a lee shore near Madagascar in

hellatious seas. Now we truly understand

why he had to do that.

In that interrupted draft I also wrote: “It's weird moving

into a huge area of coral atolls and low sand islands that mostly can't be seen

until you're close enough to see the tops of palm trees, just a couple miles at

best. And it's easy to see why they got

their fearsome reputation as the "Dangerous Archipelago" in pre-GPS

days. Without the GPS we'd be taking the

more open northern route, as many cruising boats did when celestial navigation

was the only option. Plus, currents can

run hard around the atolls, not just in the passes.”

So it’s dark and windy, and the moon won’t rise until

midnight, and we’re threading through a maze of atolls. With a turn to put the wind finally aft of

abeam, plus an alert lookout, GPS and a backup position plot on the paper chart

every couple of hours, it’s just tiring rather than difficult. The rest of the sail to Fakarava was pretty

decent, and at 4:00 am we hove-to off the North Pass, waiting for daylight and

slack tide at 7:30. We’re happily anchored

off the village in the northeast corner, but will head for the famous South

Pass in a few days.

What REALLY gets a

sailor’s goat:

Actually, it’s the calms.

In spite of the excitement of the between-atoll sail, being becalmed can

still be the most difficult, especially when a swell is running.

Witness our friends Patrick and Kirsten aboard Silhouette, a Cabo Rico 38 currently enroute from the

Galapagos to the Marquesas. We keep in

touch via email over the Ham radio, and they actually download our blog posts as a stay-awake aid on dark night

watches. Whoa—someone please tell them

about iPods and headphones!

Patrick wrote rapturously about days and days of gorgeous

trade wind sailing (which made us green with envy), but it was shortly followed

by this: “Okay, I knew it would happen,

but I sent you that note anyway. You know, the one about the marvelous trade

wind sailing we had been experiencing for the past 17 days. Well it went away.

The wind started dropping last night and it stayed that way all day today. We

tried running wing & wing and eventually got the asymmetrical spinnaker

out. Soon it was hanging limp as well. Not wanting to waste the moment I

returned to re-read one of Karen's latest posts... The one about waiting for

wind and how character building it is. I

added the character building part by reading between the lines.”

Hoo boy, now WAIT JUST A GOL-DURNED MINUTE! I wish to make it exquisitely clear that had

we carried enough fuel, we would have FLOORED IT and gotten the heck out of the

ITCZ and across the Pacific, too! But

upon re-reading the lines, the character-building implications did kinda leak

through, didn’t they. Oh well.

Patrick continued: “So

after due thought and careful consideration I did what every Puget Sound sailor

would do, I turned the key and "Vroom, the diesel rumbles to life..."

and off we went. Do I feel bad? Well I did at first, but thus far on this passage,

we had hardly used any fuel since leaving the Galapagos. In fact we had to this

point only run the engine for motive power a bit getting out of the harbor and

clear of the land and the balance to charge batteries when the cloudy days

prevented the solar panels from keeping up. We had spent the past 17 days

actually sailing, day in and day out. What to do, what to do? I didn't want to

let Karen down! OK, I've got it. I

realized the batteries hadn't really had a "full charge" in over two

weeks so I'm doing it for them. That's my story and I'm sticking to it. My

conscience feels clear already.”

Ahh, we thought, he is wrestling with monumental stuff

here. Rationalization is a perfectly

good tool for that.

But then ANOTHER note:

“Barely an hour after confessing to Sister Karen that I was weak and had

succumbed to the Siren call of the diesel, the wind returned. Not to its former

level, but usable. Using it we are, even though the batteries aren't fully

charged. Bless you, Sister.”

You are forgiven for your brief lapse, Brother Patrick. The Church of the Becalmed and Pretending to

Love It welcomes you.

The Tuamotu Tutu: Seriously, wouldn’t that make a great

song? And speaking of churches, there

was quite the parade here in town yesterday.

The entire town came out for it, and all of us yachties

joined in, too. Turns out the Catholic

priest (and isn’t that a lovely church?) told his flock that instead of

spending Sunday afternoons online ordering Costco goodies, they should all be out

making a joyful noise. They took him up

on it.

Leading the parade was this truckload of smiling drummers,

followed by a truckload of guitar players whom no one could hear because the

drummers were so loud. They drove down

to a crowd of about a hundred fifty people led by a white and gold phalanx of

priests, with children scattering flowers from palm baskets along the path in

front of the procession.

There were some very good and enthusiastic singers in that

group, and it was a joy to listen and sing along—though my efforts probably

sounded like a two year-old’s version of their language. They were having a lot of fun. The next altar, the same thing. We realized that these altars were probably

like stations of the cross, of which there are a LOT to be spending 15 minutes

at apiece, so after the third round we and our buddies Don and Deb from Buena Vista walked back to the

dinghy to spend the evening together on Sockdolager,

making our own joyful, Margarita-fueled noise.

Here are Deb and Don Robertson and Karen, trying but not quite succeeding, to behave in church.

Here’s a sweet little Tuamotan cottage.

We’ll relax here a bit more after the passage, then will

head for Fakarava’s South Pass, where all those cute little sharks live.

Very instructive about sailing the Dana upwind. Thanks!

ReplyDelete